Tim's Notebook

Tim Larsen

tim@timsnotebook.com

831 704 7747 home

669 221 0573 cell

I started out as a painter. A major drawback to painting is that it freezes everything in the picture plane to a moment of time and space. One can't see what happens next, or move to other areas in the environment depicted. One is rooted firmly where they are in a painting.

Not so with comics. Time and space are opened up in a truly remarkable way. Comics are best when one has a feeling of participating in the world that the characters live in. You don't read a comic book as much as experience its reality and know its characters.

In that way comics are a cross between literature and film, but in a more personal way.

My wish as an artist/illustrator is to find interesting and compelling stories to work on (for money of course), and develop my craft while stretching my boundaries. I've always felt that good writing is the key to quality work. It's well crafted characters and believable interaction that retains a readers interest. I understand how hard writing can be, there's a lot you don't see in the endless drafts, revisions and polishing of dialogue and characterization. Not to mention all the research that goes into filling in the details.

What follows is a step-by-step run through of how a comic book is produced with me as your artist:

When a comic book is finished it needs each page to be a large format high resolution file, as well as the cover. There also are filler pages like the inner cover, back page etc. From there a smaller format page such as a pdf is created so that the writer and artist can see a fairly accurate 'mock up' of the finished look. A pdf viewer like Adobe can group the pages so that the first page stands alone on the screen, subsequent pages appear with the even one on the left and the odd one right. Arrow keys function as page turns. Pdfs may be converted to jpegs for web browsing and viewing on tablets.

Therefore, you have three main formats: Adobe Illustator, PDF, and JPEG to consider when making and compiling pages.

Tell me your story. Pretend I'm the reader you're trying to court. I want to hear your pitch. Make sure your story is a complete tale with the ending included! It's important I get the sense of story you're trying to convey and effect it has on people. Does it have a hook? Would it hold the attention of a reader who may not be normally interested in your subject?

After the initial contact, a writer and I agree to certain terms of production goals and payment. Basically it covers how far your story needs to go and how much of it you can finance. Is it a teaser consisting of five pages or so? Is it a typical 'floppy' in length, about 20 - 22 pages? Will it be a major serialized Graphic Novel covering 100-plus pages? How many can you afford and when can you pay for them? Color? Black and White? Grey washes? Cover included?

All that needs to be put down in writing as a contract covering all contingencies. Here's a link to a simple contract I've devised. I try to keep it on one page and cover just the essential information that protects both the writer and artist. It just says what will be done and when and who owns it once it's finished (typically the writer).

One final word about the contract. It will contain a requirement for a deposit. The day the deposit is paid defines the beginning of the project. It's the starting gun, all deadlines and time tables derive from that moment!

You can start anywhere. All I need to see is some kind of a scripted story told in a format that's fairly consistent. The important thing is to pick up early a sense of plot and pacing, focusing on the reader's experience. The sript can be in any format, but mainly most writers break it down to scenes and dialogue.

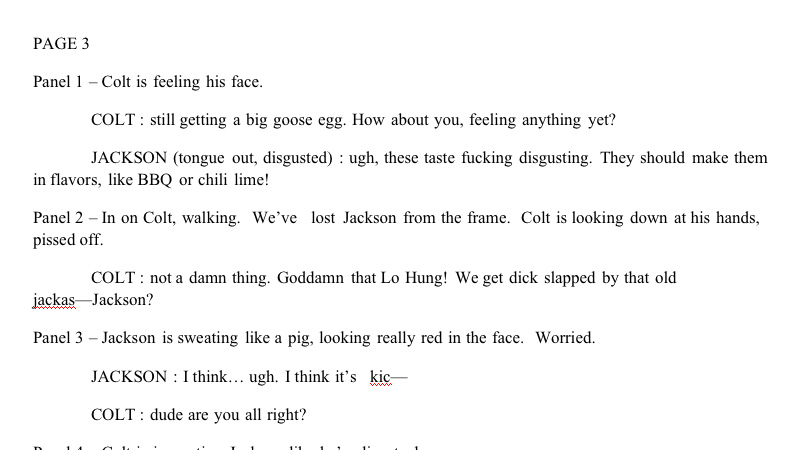

An excerpt from Double Barrel issue three by Patrick Self and Greg Loyd as written by the author.

To the left is the original script for Double Barrel by Patrick Self. He furnished me several pages of scenes panels and dialogue. Here he has a scene with his two main characters falling under the effects of eating psychedelic mushrooms. The dialogue is slangy and character-specific, and the action flows along fairly well.

At this stage it's the rough draft, something to work with and polish. One has to think of telling their story in still images. Each image builds information that fills out a scene. Each scene is a section of your comic book.

An excellent resource for script writing can be found at comixtribe. The link goes straight to their history page going back about two years with many informative articles about producing comics, with emphasis on writing and strategy. I strongly urge anyone who's serious about pursuing creating comics to go there!

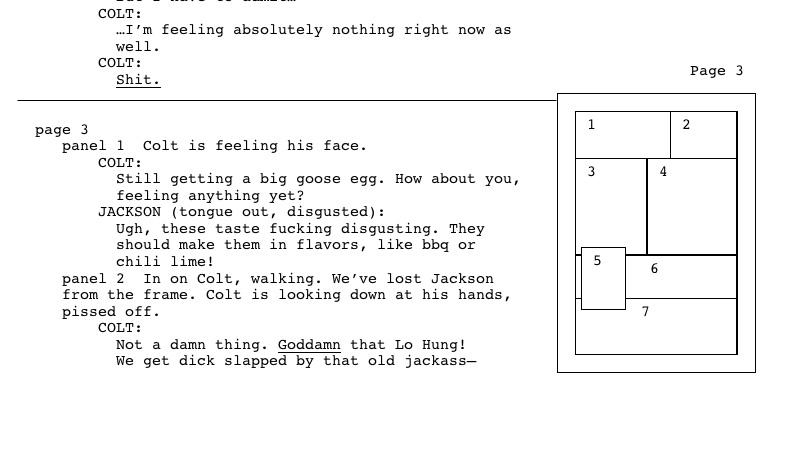

An excerpt of the same page re-formatted.

Here's the modified version that I did.

The page numbers, panel numbers, panel description, character's names and dialogue are ordered using an outline system that allows for editing and saves time. In other words, I'm not actually writing 'page one' or 'panel three' etc. The software does that for me.

The advantage to using outlines is that whole blocks of material can be easily inserted, edited, deleted, or moved up and down. Page breaks are shown as a solid line across the document, along with a small thumbnail mock up of the page itself. Inside the mock up are numbered panels.

I've developed this method of script writing and so far it's been fairly useful for me to make a clear cut preview of how the pages will unfold. You get a feel for the flow of the comic book. One small way I deviate from the norm is using the solid line instead of a page break in the document itself. That's a personal preference of mine, but I do make a page break to save a panel from being cut in two.

Formatting scripts is something that I charge for since it does take some time.

Now we're getting somewhere. A file sharing account is started in Dropbox. That's where the script and the (slowly) building comic takes shape page by page in pdf format. A pdf is convenient -when the page layout is set to 'facing'- for looking at the pages as they would appear in the comic book.

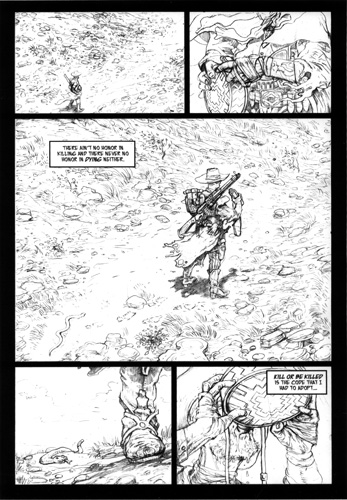

The pages are mocked up in pencil first, with lettering laid in. Penciled pages are added to the completed pages as they are done. Once the penciled pages are approved I can move on to inking and coloring them.

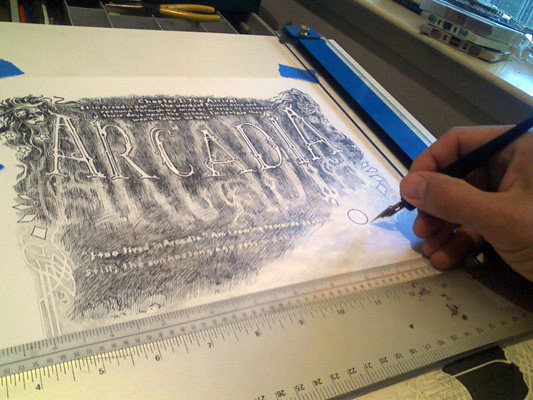

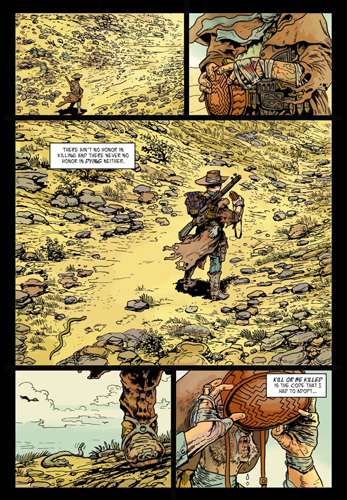

penciled and lettered page from Dustbowl

finished page.

A special note. When pages are done I hold on to the finished pdfs until paid, but I do show them to you in a quick email attaching them as thumbnails.

This is to prove the work was done, and to ensure I'm not handing over something that's usable to you right away. Think of it as the merchandise inside a display case, you can see it, and you can have it as long as you pay for it..

It starts to take shape. As the pages get finished and added to the ever growing pdf being shared in Dropbox we get closer and closer to the finished product.

Abandoned the project? Stopped paying? That's what the deposit is for. I keep that until everything is paid for and up to date. When the last pages are done I hand over to you the whole she-bang in high resolution files for each page in Illustrator. It's delivered either in Dropbox again -or burned onto a cd or loaded onto a flash drive that I can mail to you. The high resolution files are important, in that it's what's needed to get the work printed.

Awright! You got a comic book now! Now's the moment you have to insert it into your publicity machine... ...I assume you have one? No? It's okay. There's several avenues to pursue, again, sites like comixtribe can offer you endless ideas and advice from pros who have made it.

Trying to contact publishers nowadays has been phased out somewhat. True, you can look up the Image or Dark Horse websites and they will have submission forms and guidelines. You have to remember they promote properties that make money for them and usually don't grant even finished work a chance unless its proven to be successful already.

So how are you going to get attention to your comic and/or raise sufficient funds to keep it alive?

Kickstarter.

Kickstarter is a useful avenue for generating buzz and gathering together people who would be interested in investing in your idea. If you haven't heard about it already, Kickstarter is crowd funding site that lets you put together a sales package to potential customers. They pledge a certain amount of money to receive a finished product of some kind. It can be your actual comic, or collateral material related to it (original art, posters, t-shirts etc.)

The one caveat is that once your campaign goes live you have 30 days to fulfill your fundraising goals or else you don't get the money. It's a good idea to use a lot of planning to be sure you're making a goal that's reachable. Maybe you have a ten issue story arc that would require $40,000 to fully fund, but realistically can put together a well written and illustrated (by me of course) first issue for $4,000. You can always build momentum on the first issue and return to kickstarter for another round.

Comixology.

Comixology is a digital marketplace for finished comics that people can view on their tablets or computers for around 99¢, maybe more if the story is larger.

They take a percentage from the sale and pool the profits. You get a payment for any amount over $100 each quarter, under $100 and it carries over to next quarter.

The two big houses Marvel and D.C. have been actively pushing their product for years this way, and digital is an absolutely cost effective way to bring your readers to your story.

There's an added advantage of people buying older digital issues. Once you start publishing newer comics digital back issues are a convenient way for them to catch up.

There is a submission process and you do have to get approved. You have to have ownership of your idea and it has to be of a certain quality where they feel people would want to buy it (again, a no brainer if you have me as your artist).

Suppose you have finished artwork that can fill out a full story but don't want to publish it big time, just need a few issues to pass around at conventions?

Ka-blam.

Ka-blam can print your comic for under $2 a single issue.

Ka-blam is a powerful way to level the playing field and bridge that gap to bring printed material in the hands of your readers while not risking a large amount of money.

Another advantage is you're able to put a copy in your hands to proof before going ahead with a large print run. For a lot of people they are unsure what the finished product will be like until they see it in physical form, once they have it they may have some minor alterations to make: more pages, different color, insert pages, etc.

To sum up... ...there's no excuse for not having your work available in some form or another. A lot of creators find time to write, edit and pay for art but have no gas left in the tank in getting to the public. Don't be one of them! It's strongly recommended for any one planning to have a back-up contingency, and maybe another back-up in case the first one fails. You have a story in you. Hiding it in a file somewhere on your lap top shouldn't be its ultimate fate.